Borisav Matić: The 25th Mladi Levi Festival – independent, international, optimistic

August 30, 2022

SEEstage magazine

article by Borisav Matić

The 25th edition of Ljubljana’s Mladi Levi Festival featured an international programme of theatre and dance. Borisav Matić looks at some of this year’s highlights

Ljubljana’s Old Power Station is located in a residential neighbourhood near the city center, signalling its position with its tall factory chimney which can be seen from the surrounding streets. The building is not just a preserved artefact of late19th-century industrial architecture but also a space for theatre and dance, rehearsals, workshops and other educational programs.

The artistic program of the Old Power Station has been managed by Bunker, a Slovenian non-profit cultural organization, ever since 2004. The Old Power Station is also the central location and, in a way, a backbone of the international performing arts festival Mladi Levi (Young Lions) which is organized by Bunker at the end of each summer. This year’s edition, which took place between 19th to 27th August, celebrated 25 years of the festival’s existence.

From the Power Station where most of the performances are held, festival meals are served and guests socialize, Mladi Levi further disseminates to several other theatre venues and outdoor public spaces in the city. If you live in or are visiting Ljubljana, the festival is hard to miss, and not just because of its

geographical diffusion throughout the city, but because of the scope and relevancy of its program.

Most of the productions (all of them in the case of this year’s selection) come from independent artistic scenes of various countries – European (Slovenia, Croatia, Serbia, Italy, Germany and Belgium), South American (Chile, Columbia and Mexico) and Asian (Thailand). The festival is also affordable – because Bunker charges only a symbolic one Euro for each show ticket.

Dance Me to the End of Time

Among three dance performances that were presented at the 2022 Mladi Levi festival, Bodybodybodybody was the one that ecstatically opened the festival, transferring a burst of energy from the stage to the audience. Inspired by a Southern Italian folk ritual where the locals would frantically dance to get rid of the evil spirits, Dag Taeldeman and Andrew Van Ostade (the creators of the show) composed a piece of modern ritualistic music to which the performer Matteo Sedda dances. The music is an eclectic mix of electronic sounds, drum, bass and vocals that start from simple repetitive forms, but ultimately result in a crescendo when the opera singer Lies Vandewege joins the rhapsody. The performer dances in positions to the music, but always repetitively and energetically demanding until he starts dripping sweat everywhere around him and collapses on the floor by the end.

The contemporary ballet piece by Alessandro Sciarroni, TURNING_Orlando’s Version, was also presented at the festival and one could argue that there are a lot of similarities with Bodybodybodybody, even though the type of dance is different. This 45-minute performance also nurtures the love of repetition, so the six dancers mobilize their steady movements to show us many different ways how ballet dancers can turn around their axis and around the performing

space.

But if TURNING_Orlando’s Version is a meditation on ballet movement, Save the Last Dance for Me – another of Sciarroni’s performance at the festival – is a formally complex dance and fast dance made to induce passionate feelings both in the audience and among the two performers (Gianmaria Borzillo and Giovanfrancesco Giannini). Save the Last Dance for Me is a recreation of Polka Chinata, an early 20th century dance from Bologna that peaked in popularity after World War II, but almost became forgotten in the 21st century. The artists not only saved the dance from extinction by performing it and giving Polka Chinata workshops (two such workshops were also held at the festival), but they also cleverly play with the meaning of the dance. While the original

Polka was always played by two men who showed off their dancing skills in order to attract women, Borzillo’s and Giannini’s attention is more focused on the relationship between themselves. So, when they start smiling at each other while clearly enjoying the dance, the audience sees a possible queer relationship at the center of the dance.

Art Stikes Back

While the 25th edition of the Mladi Levi festival showcased contemporary dance trends, it also shone a spotlight on socially engaged art. Perhaps the best example of this is Julian Hetzel’s show All Inclusive which deals with ethical questions of (re)presenting war traumas in art. Concretely, the show thematizes the hypocrisy of the European artistic establishment that insensitively uses the narrative of the Syrian war for their own benefit, while retraumatizing refugees and violence survivors. This complex question is represented in the story where a group of refugees (played by actual refugees and non-actors) comes to a European contemporary art museum where a curator (Kristien de Proost) leads them through an exhibition that thematizes violence and war. „This may seem bizarre, but this is art,” she tells them, showing them model rockets made from rubble from war-torn Syria, or showing them porcelain dogs and asking them to pick a favorite one and then smash it with a hammer, so they can create art through destruction.

While All Inclusive is wild in its dark humour and absurdity, Out of the Blue by Silke Huysmans and Hannes Dereere is an example of a different, yet equally poignant socially engaged show. It is investigative journalism at its best presented in the form of documentary theatre. Huysmans and Dereere investigated the topic of deep-sea mining for minerals that are essential for creating green technology and transitioning from fossil fuels. Yet, deep-sea mining, currently only in the preparation stage, has the potential to eradicate unique animal life at the bottom of the option.

The creators of Out of the Blue interviewed numerous experts on this topic, but also activists and representatives of a Belgian mining company. During the whole show, Huysmans and Dereere are silently sitting on the stage, backs turned to the audience, while we watch them carefully pick and present the audio-visual material on big screens on the stage. This transparent technical process aims to show that every narrative is a constructed one, including those in documentary pieces and that the audience should be critical of everything they see and hear.

Among other socially engaged shows at the festival – although the list doesn’t end with them – are Minga of a Ruined House and Mutilated by Chilean artists Ébana Garín Coronel and Luis Guenel Soto. In both shows, artists tell stories of social unrest in Chile, but through the lens of stories about particular objects. In Minga of a Ruined House, Ébana Garín Coronel tells the story of her family’s exile in Ecuador in the 1980s during the Pinochet dictatorship, but the story only

occasionally surfaces while the primary focus is on the Minga, a tradition on the Chiloé Island in Chile where locals move or sometimes even destroy their houses if, for example, the neighbourhood is being gentrified or the person needs to move because of work. There is a contrast in the show between a narrator who is forced into exile and the locals on the island who have their homes but choose to destroy them. On the other hand, Mutilated tells the story of the protesters who lost their eyes during the 2019 Chilean demonstrations against economic inequality. The political struggle is this time shown, at least partly, through the story of old satellite receiver dishes that protesters end up using as shields from the police bullets.

The Young Lions

Given that the name of the festival translates as “Young Lions”, Bunker creates a special space for young talent in its programming. Minga of a Ruined

House and Mutilated are not just politically engaged shows, but also examples of Bunker’s support for the art made by young artists. Fasciarium, a show by the Columbian artist Susana Botero Santos, is another example. Fasciarium also proves that young artists can create theatre works that are very simple in form and content but also very cathartic. The show has two parts, the first of them being a lecture performance by Susana Botero Santos – she narrates about her coming of age in a conservative and Catholic environment where any relationship a person has with their body is stigmatized and sexual harassment and judgmental looks are always around the corner. After this fragmentary monologue, the second part of the performance is pure flamboyance where the audience is invited on stage and where a group of “human creatures” is ready to transform their bodies if they are not satisfied with them. “Human creatures” – dressed in layers of fabric and ornaments from head to toe – gradually dress the audience and engage in various games with them, until everyone is invited to party hard together for the last 15 or 20 minutes of the performances when all stigmas disappear and “weirdness” becomes the norm.

If Fasciarium ended in a beautifully weird way, Love, Feathers and Javier Solis started in a way that many in the audience saw as awkward. The Mexican artist Daniel Alberto started this solo performance by throwing different objects around the room with no explanation. He also jumps around the room from tables and chairs and intends to push lighter objects in the air with a hair dryer. What later turns out is that the whole performance is the examination of flying and that Alberto spent and an excessive amount of time watching YouTube videos about flying as the research process for the performance. Some members of the audience later become involved in the performer’s games and in asking for help from the audience, Alberto attempt to overcome the existential questions that he felt after the intense research on flying.

article by Borisav Matić

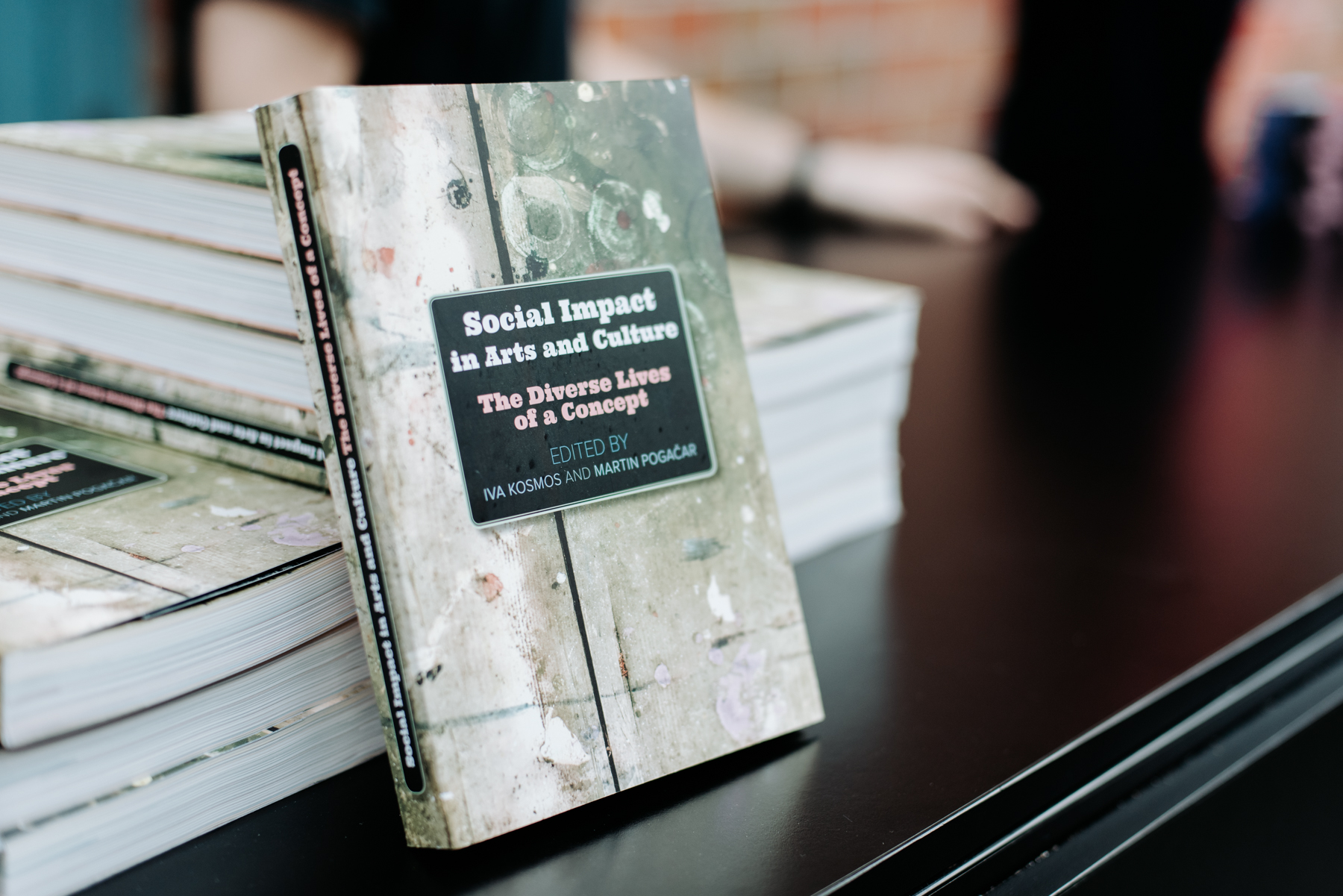

The closing event of the Create to Connect –> Create to Impact project was also held during the festival. Create to Connect –> Create to Impact (CtC -> CtI) is a pan-European project led by Bunker in partnership with 15 European cultural organizations. It began in 2018 and ends on the 31st August 2022. Many of the performances presented at the 2022 Mladi Levi festival were created thanks to the support from this project, including Fasciarium, Minga of a Ruined House, Mutilated and Love, Feathers and Javier Solis. The aim of the project was to create a social impact in European societies through art and culture. The representatives of Bunker and the project partners presented the main outcomes of CtC –> CtI at the closing event but also presented the project-supported publication Social Impact in Art and Culture: The Diverse Lives of a Concept.

What social impact art and culture have is a question that will find many answers in this publication given that it was based on contributions from 17 authors (it was edited by Iva Kosmos and Martin Pogačar). But what Iva Kosmos noted during the presentation of the book could be one of the poignant answers to this question – after the collapse of the welfare states in the second half of the 20th century, one of the functions of art and culture (as well as NGOs and practices like volunteerism) is to fill the void after the social transformation. It could be said that the Mladi Levi festival has, among else, exactly that function – to create social critique through politically engaged performances, give spaces to young artists and cultural workers and promote contemporary artistic tendencies. If the institutions have failed in these tasks, then the independent scene must pick up from there.

Original article was published in SEEstage magazine.

photo: Branka Keser